Property cycles are driven in part by the business cycle. In good times, a buoyant economy sees businesses expanding, demand for space increasing and vacancy rates falling.

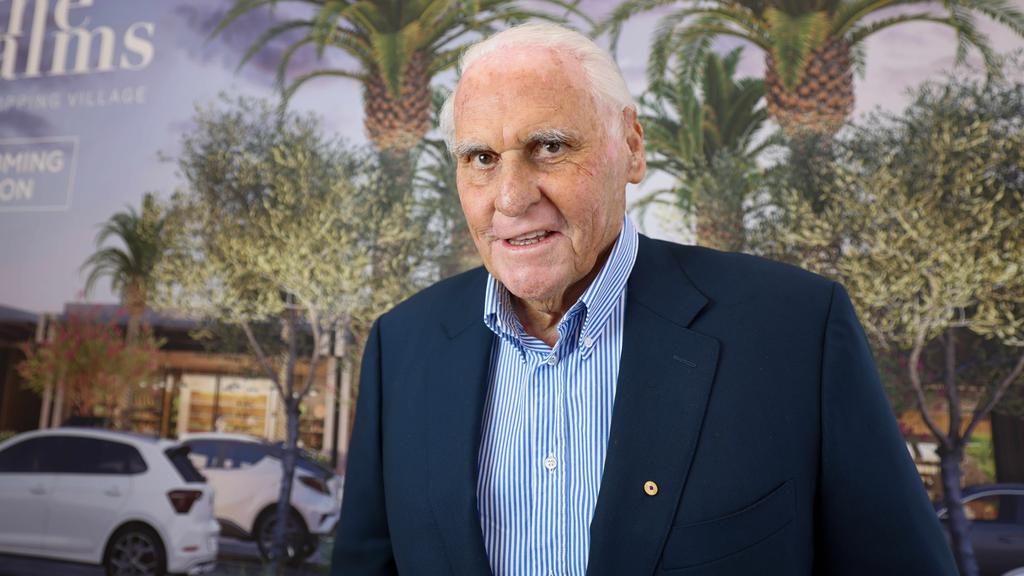

The recent passing of Lang Walker, one of Australia’s most successful property investors and developers, has undoubtedly prompted many in the industry to reflect on how he navigated the commercial property cycle over the past 50 years. And how the tycoon would be positioning for the next phase of the cycle.

For those who had the fortune to hear Lang talk about cycles, you were always struck by his views on the dynamic nature of property markets and the need to respond to ever-changing market conditions. He also pointed to the need for a balance between patience and readiness.

In 2004, he succinctly put it: “There are years when you are better off sitting on your hands, and then there are years when suddenly you have opportunities falling out of the trees.”

For those who entered the industry post the global financial crisis, and some of whom would now be in senior positions across the industry, the recent downturn marks their first experience with rising cap rates and falling commercial property values.

Property cycles are driven in part by the business cycle. In good times, a buoyant economy sees businesses expanding, demand for space increasing and vacancy rates falling.

But it’s the capital (credit) market cycle that is just an important driver of property cycles. Capital flows can at times overwhelm property fundamentals.

The property downturn of 1990-91 were primarily driven by an oversupply of property fuelled by easy credit. Demand surged, initially outpacing supply. As property prices rose, development became even more lucrative.

And developers expected continued price increases, so supply continued to ramp up.

But eventually, the market went into oversupply, leading to a price correction.

Sydney and Melbourne CBD office values fell by circa 40 per cent and 50 per cent respectively between December 1989 and December 1993. It was a similar story in the industrial sector, with Sydney industrial values declining by about 35 per cent and Melbourne industrial by about 25 per cent. But the fuel on the fire in the lead-up to the 1990-91 downturn was the deregulation of the financial system in the 1980s and the resultant abundance of credit from both domestic and offshore banks, which funded the mass overbuilding.

Several banks were caught out.

In the depths of the early 90s property crash, the State Bank of Victoria was bailed out by CBA and Westpac was close to collapsing after the value of its property loan book was slashed by a staggering 40 per cent.

Walker Corporation founder and executive chairman the late Lang Walker. Picture: Russell Millard

Debt is great on the upside, but unforgiving on the downside as the property sector found out during the global financial crisis in 2008-2009. When the global credit markets froze, many listed A-REITs, unlisted property funds and syndicates, and developers who had taken on excessive leverage were caught out.

The impact was most apparent in the A-REIT sector.

High leverage coupled with international expansion and poor currency hedging strategies, and payout ratios of more than 100 per cent of free cashflow sent A-REIT prices plummeting.

Many A-REITs were forced to undertake deeply discounted rights issues to raise equity capital to survive – GPT did a raising at a 45 per cent discount and Mirvac at a 34 per cent discount to their five day volume weighted average price.

Some A-REITs didn’t survive after the GFC; they were either taken private or taken over by other REITs – Challenger Kenedix Japan Trust, Macquarie DDR Trust, Multiplex European Property Fund, Rubicon America Trust and Valad Property Group to name a few.

Coming into this down cycle, the major Australian A-REITs and unlisted funds learned a valuable lesson from past cycles: don’t overuse leverage. By and large, the institutional end of the Australian market has been well-positioned to absorb the rapid rise in interest rates from historical lows and service their debts.

Consequently, as both listed and unlisted property markets adjusted pricing in response to the sharp interest rate rises over the past 18 months, we haven’t seen the stark headlines about offices landlords handing back the keys to properties that have hit the US. And as we enter 2024, while uncertainty lingers, there are signs to be optimistic.

Inflation appears to be moving in the right direction and cash rates look to have reached their peak, although the timing of interest rate cuts remains uncertain.

Geopolitical risks do remain high. However, Australia appears poised to sidestep a recession, with the economy on track for a soft landing and population growth remaining strong. With A-REITs still trading at discounts to NTA – although the recent rally has narrowed the gap – the listed market is still signalling that the direct market has some way to go in repricing.

Suffice to say, that the process of realignment in the direct market continues, albeit the magnitude varies across sectors and from market to market. Despite a softening in demand across most sectors, occupational markets remain relatively resilient due to some tight supply conditions caused by high construction and debt financing costs.

Adrian Harrington, NSW Chair of Housing All Australians.

Transaction activity has been subdued as the bid-ask spread between buyers and sellers has been wide.

Nevertheless, as investors gain greater clarity in the timing of interest rate cuts and grow more confident in key underwriting assumptions such as return requirements and rental growth expectations, transaction activity is expected to increase this year.

As capital returns to the market, the alternative sub-sectors will be a key beneficiary. The inherent tailwinds stemming from demographic shifts and technological advancements present compelling opportunities in sectors such as living (build-to-rent, student housing, manufactured housing), life sciences (medical centres, hospitals, biotech labs), and data centres.

Industrial will continue to do well, supported by positive structural thematics of supply change management and e-commerce. Demand is expected to moderate from record levels and vacancies will tick up, albeit from a historically low base.

And do not discount offices entirely – they will make a comeback. CBD vacancy rates have moved up to levels not seen since the early 1990s. Now is the time when the market will continue to bifurcate with prime assets leading the way.

Retail had fallen out of favour with investors long before the recent interest rate hikes. But again, green shoots are emerging as mall landlords learn to adjust to the impact of e-commerce, while new supply remains constrained.

The key for the retail sector will be how long consumers endure cost of living pressures. Even if the RBA cuts rates in the latter part of this year, one thing we should anticipate is that the availability of ultra-low-cost capital is unlikely to be back to fuel the cycle’s next phase.

As ever, the cornerstone of any successful investment will be meticulous asset selection and active asset management.

The key will be prioritising high-quality assets supported by robust fundamentals such as location, tenant covenant, and lease structure, rather than relying on cheap debt and financial engineering.

Investors may also pursue value-add strategies, targeting assets with high vacancies or repositioning potential.

History shows that the most favourable investment opportunities tend to emerge in periods in the wake of disruptions, marked by major shifts in economic growth, interest rates, and property market conditions.

Taking a leaf out of Lang’s playbook – will this be a year of patience, or will it mark the time when opportunities indeed start falling from the branches?

Only time will reveal the answer.

Adrian Harrington is a Senior Adviser to Lighthouse Infrastructure and NSW Chair of Housing All Australians